Wares produced for Indian and Other Islamic Markets

Although the quantities originally produced were fairly large, few examples of Chinese export porcelain for Indian and other Islamic markets are known in Western collections. The Nadlers’ special focus on such porcelain provides a rare opportunity to study wares of these types. Although some patterns were also popular in the West, porcelain in this group often has a unique flavor. Arabic inscriptions are an obvious clue to help identify original consumers; enamel colors such as rich greens and pinks from the famille rose palette were often particularly favored.

Although the quantities originally produced were fairly large, few examples of Chinese export porcelain for Indian and other Islamic markets are known in Western collections. The Nadlers’ special focus on such porcelain provides a rare opportunity to study wares of these types. Although some patterns were also popular in the West, porcelain in this group often has a unique flavor. Arabic inscriptions are an obvious clue to help identify original consumers; enamel colors such as rich greens and pinks from the famille rose palette were often particularly favored.

Similar figures of mahouts (elephant drivers) can be seen on at least three services with different borders made between 1760 and 1790 for British colonials in India. This type of Chinese bianco sopra bianco (white-on-white) border ornament was imitated on Western porcelain and delftware.

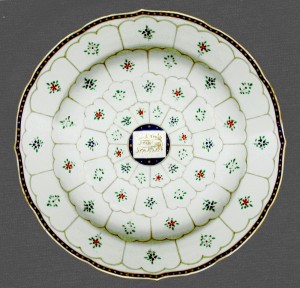

Dish, 1790–1830

The colors and ornamental motifs on this saucer-shape dish indicate that it was produced for the Indian or Asian market. Compare the colored enamels on the bowl, spoon, and dish made for Nawab Feizsalar of India, shown below.

Bowl, spoon, and dish from services made for Nawab Feizsalar of India, 1824

The Urdu inscriptions on the dish and bowl translate as “His Excellency Nawab Feizsalar and [his] Begum Shahibe, AH 1239 [or 1824].” An abbreviated version is seen on the spoon. The Nadlers acquired the green dish in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar; a pink-ground dish from the same service in New Jersey; and the bowl and spoon in New Delhi, India.

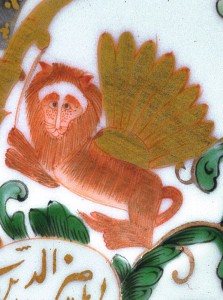

Dish bearing arms (probably) of Bahadur of India, about 1820

Dish bearing arms (probably) of Bahadur of India, about 1820

This pattern was inspired by a Worcester porcelain design first made in 1762. The Urdu inscription (translated) “Vizier of the Kingdom, Right [arm] of the State, Bahadur” probably refers to Bahadur Shah II, the last Mogul emperor. A similar service was given by the Sultan of Malacca to a Dutch navy man named Constantijn Johan Wolterbeck around 1818.

Dish, 1790–1810

This dish bears a flowery inscription in Farsi (translation): “Governor, Leader, Supporter of the State, Prince, Glorious and Beneficent Reza Khan.” Although lotus-like patterns were popular over a long period, the dish is datable in part based on the type of narrow blue border.

This bowl is twice-inscribed in Arabic (translation): “Eat, Drink, and Be Sated.” Acquired by the Nadlers in Istanbul, the bowl may have been produced for the Near Eastern or North African market, both of which were part of the Turkish Empire.

For now obscure reasons, this popular motif is known as gol ve bulbul, or, the flower and the nightingale. Perhaps the nightingale flew away? Similar designs can be found on dinnerwares and beveragewares made for the Persian market. This teapot is one of a pair in the Nadler collection.

Jug perhaps made for Osman Nuri Pasha of Turkey, 1865–80

Jug perhaps made for Osman Nuri Pasha of Turkey, 1865–80

Helmet-shape jugs were popular in nearly all markets. The Turkish Arabic script on this Japan pattern jug honors “His Excellency, most high, Othman Pasha . . . may God grant him long life,” which perhaps refers to Ottoman field marshal Osman Nuri Pasha, a hero of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78) who was later Minister of War.

Plate, dated 1833

This plate is decorated in one of the most popular Persian market patterns. The Shiite benediction, at the center, translates as “Aly is looking upon you. AH 1249 [equivalent to 1833].” The name Aly may refer to a Shiite Moslem imam, or holy leader.

Bowl made for Grand Khedive Said Pasha of Egypt, about 1853

This rose medallion bowl is inscribed in Arabic (translation): “Country of Egypt, May Its Power & Glory Live Forever. Holy month of Ramadan 1270. For His Excellency the Just and Most Powerful Ruler and Grand Khedive Said Pasha.” Written on the underside in Farsi script is the following (translation): “manufactured in the factory of Haji Zein el Abedi, the Shirazi [Persian] merchant 1270 [or 1853].”

Dish with insignia of Nasr el-Din Shah of Persia, about 1865

One panel on this rose medallion dish is inscribed (translation): “The Sultan, son of the Sultan, the Monarch, son of the Monarch, Nasr el-Din Shah, Qajar.” (For ornamental reasons, the “ns” in are arranged at the bottom of the inscription.) The huge bowl shown below bears portraits of Nasr el-Din Shah and his sons.

Bowl made for Nasr el-Din Shah of Persia (Iran), about 1865

Bowl made for Nasr el-Din Shah of Persia (Iran), about 1865

This large and impressive bowl bears portraits of Nasr el-Din Shah, king of Iran’s Qajar dynasty, and his two sons. The importance of the family line is reflected in the Arabic inscription (translation): “Nasr el Din Shah Qajar, the Sultan, son of the Sultan.” A mauve-ground bowl, shown nearby, was made for the sultan’s oldest son.

Bowl made for Zil el-Sultan, Governor of Isfahan in Persia (Iran), 1879

Bowl made for Zil el-Sultan, Governor of Isfahan in Persia (Iran), 1879

This bowl–once part of a large service which included stacking bowls–displays the rare mauve enamel ground favored by Masoud Mirza Zil el Sultan al Dowla. His abbreviated name is included in the Arabic inscription (translation): “Masoud Mirza al-Sultan, A.H. 1287 [or 1879].” Zil el-Sultan’s portrait and those of his father and brother can be seen on the above bowl.